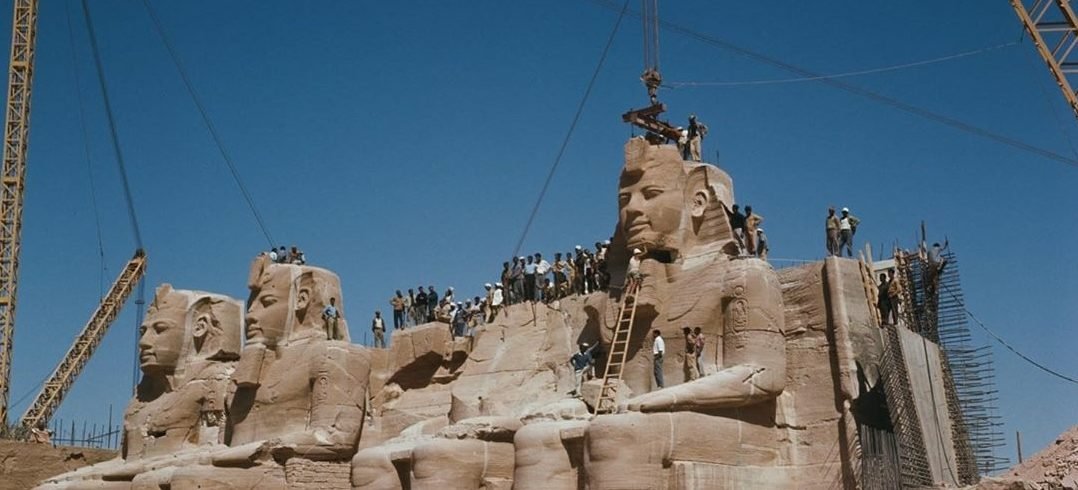

Abu Simbel temples were built by the mightiest pharaoh Ramses II, with four massive colossi of himself adorning the facade, Abu Simbel is the most famous of the ancient Egyptian monuments after the Pyramids and the Sphinx. It marked the limit of Egypt’s domain and was intended to convey the might of the pharaohs to any who approached from the south. More than 3,000 years later, it has lost none of its power to inspire awe.

Although it has the appearance of being a monument raised to the glory of its builder, Ramses II (1279–1213 B.C.), the temple was dedicated to the gods Re-Harakhty, Amun, and Ptah. Carved from the mountainside on the West Bank, of the Nile, it was begun in the pharaoh’s fifth regnal year but was not completed until his 35th. With the passing of the great age of the pharaohs, the upkeep of the temple was forgotten, and it gradually became almost completely buried in the sand. It disappeared from history completely, mentioned by neither Greeks nor Romans, until its chance rediscovery by the Swiss explorer John Lewis Burkhardt in 1813. As he described the scene, “An entire head and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues emerge still above the surface. Of the adjacent statue, there is almost nothing to be seen, since its head has broken off and its body is covered in sand to above shoulder level. Of the two others, only their headdresses are visible. It is difficult to decide whether these statues are seated or standing.” With such a huge volume of sand piled up against the temple, initial efforts at clearance were limited to finding a doorway to gain entrance to the temple and see what treasures lay within. In 1817 the Italian adventurer in the employ of the British consul, Giovanni Belzoni succeeded in digging his way inside.

Although it has the appearance of being a monument raised to the glory of its builder, Ramses II (1279–1213 B.C.), the temple was dedicated to the gods Re-Harakhty, Amun, and Ptah. Carved from the mountainside on the West Bank, of the Nile, it was begun in the pharaoh’s fifth regnal year but was not completed until his 35th. With the passing of the great age of the pharaohs, the upkeep of the temple was forgotten, and it gradually became almost completely buried in the sand. It disappeared from history completely, mentioned by neither Greeks nor Romans, until its chance rediscovery by the Swiss explorer John Lewis Burkhardt in 1813. As he described the scene, “An entire head and part of the breast and arms of one of the statues emerge still above the surface. Of the adjacent statue, there is almost nothing to be seen, since its head has broken off and its body is covered in sand to above shoulder level. Of the two others, only their headdresses are visible. It is difficult to decide whether these statues are seated or standing.”

With such a huge volume of sand piled up against the temple, initial efforts at clearance were limited to finding a doorway to gain entrance to the temple and see what treasures lay within. In 1817 the Italian adventurer in the employ of the British consul, Giovanni Belzoni, succeeded in digging his way inside. He was to be bitterly disappointed; aside from a few small statues, which he took away, the temple contained none of the hoped-for treasures. Belzoni and crew turned their backs on Abu Simbel after three days and left for good. Over the next decades, periodic attempts were made by various parties to clear more of the sand away, but always it blew back. It was not until as recently as 1909 that the temple was finally cleared for good.

VISITING THE TEMPLE Abu Simbel is usually reached from Aswan. A road connects the two, although most visitors make the trip with Cairo Private Tours by flight, a brief 30minute flight from Aswan. Flights are timed to give a couple of hours at the temple before returning. . An alternative option is to join a Lake Nasser cruise. These boats moor almost in the shadow of the Ramses colossi, giving passengers the chance to view them both by moonlight and by the first light of dawn. high, the four enthroned colossi are the largest surviving sculptures in Egypt. Their hands alone, resting on their knees, are longer than the average person is tall. They sit against a flattened area cut from the mountain to resemble the sloping walls of a temple’s pylon. At the feet of the giant statues are bound captive Africans and Asians-symbolic of the Egyptian kingdom’s border foes. Either side of the king’s legs is smaller (though still much larger than life-size) statues of his mother, Tuya, his wife, Nefertari, and some of their children. Above the central entrance, between the heads of the colossi, is the figure of the falcon-headed sun god Re.

The interior of Ramses’ temple is much less spectacular than its facade. Burrowed 200 feet (60 m) into rock, it has the simplest of plans, with a large pillared hall leading to a small one, also with pillars, and a sanctuary at the rear. Nevertheless, the first pillared hall is still fairly imposing, with eight more statues of Ramses attached to columns supporting a ceiling decorated with Osiride vultures. Reliefs on the walls, some of which still have their original color, depict the pharaoh in battle. In the small pillared hall, Ramses and Nefertari are shown in front of the gods and their sacred barks. The innermost chamber is the Sacred Sanctuary, with four small statues of the gods Ptah, Amun-Re, the deified Ramses, and Re-Horakhty.

The temple is aligned in such a way that on February 22 and October 22 every year, the first rays of the rising sun penetrate the temple and illuminate the holy quartet-or at least three of them; Ptah, on the left, remains in shadow. Until the temples were moved up from the lake, this phenomenon happened one day earlier. Some Egyptologists have speculated that these may be the anniversaries of Ramses’ coronation and birth.

TEMPLE OF HATHOR

To the north of Ramses’ main temple is a far smaller second temple, built in honor of the pharaoh’s beloved chief wife, Nefertari. It is dedicated to the goddess Hathor, the deity most closely associated with queenship in ancient Egypt. It, too, is fronted by a series of colossal figures. Standing about 32 feet (10 m) high, four of these statues are of Ramses and two of his queen. Beside them are the more diminutive figures of the rest of the royal family.

Inside is a single hall with six pillars crowned with Hathor (cowered) capitals. The walls are adorned with scenes depicting Nefertari before Hathor and Mut. On the rear wall, the queen is shown as a cow with the king beneath her chin. What is striking is the importance granted to Nefertari, with the queen repeatedly shown on an equal footing with the king. As a pharaonic queen, she is unique in this respect.

A gray door in the mountainside to the right of the main temple offers quite a bizarre experience. Passing through and ascending a tubular steel staircase, you see the inside of the fake mountain, a vast domed space, filled on one side with cut-stone blocks-the reverse of the monumental facade. The effect is a little like Dorothy pulling aside the curtain to reveal the puny reality of the Wizard of Oz.

Kindly check our Tours to Abu Simbel